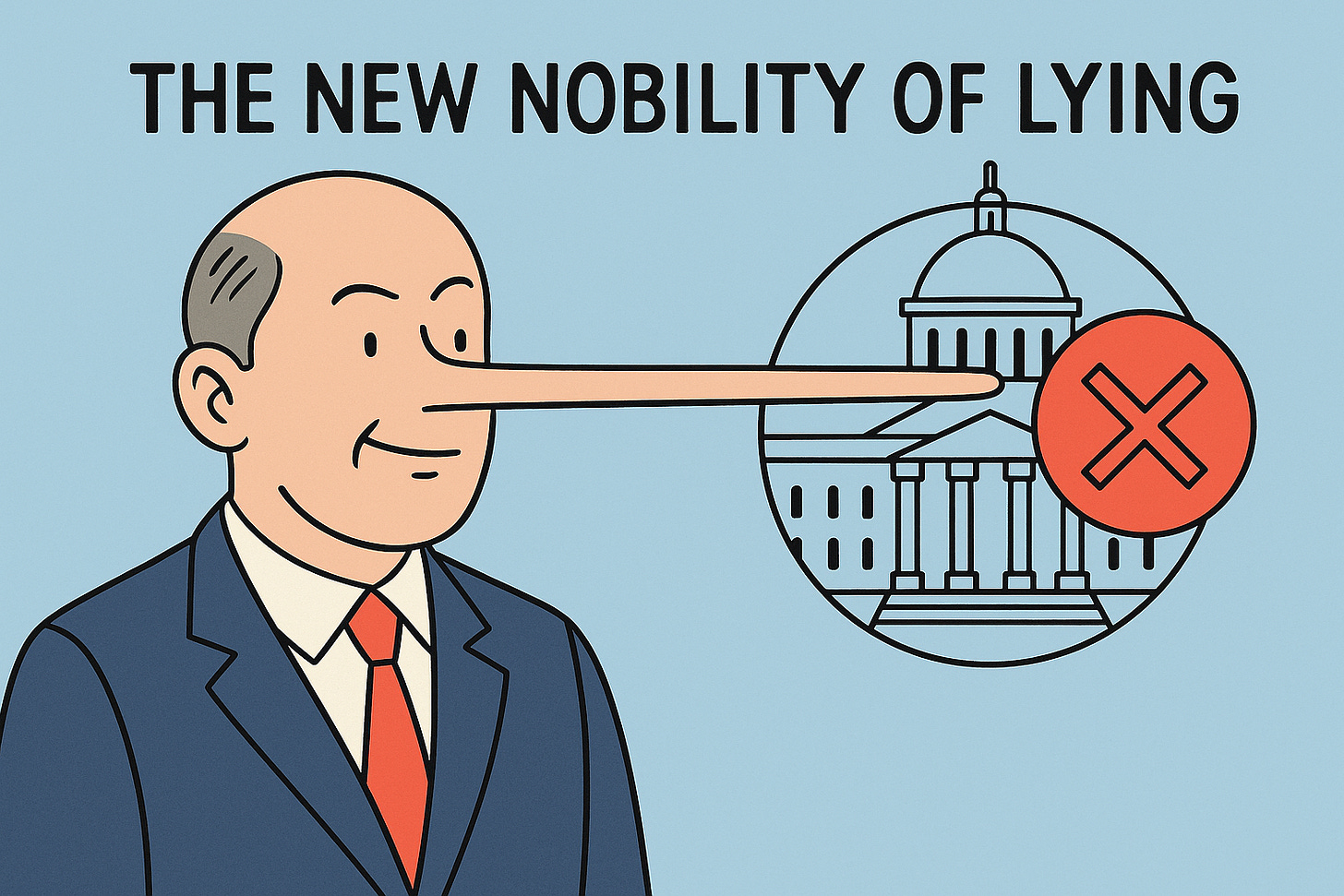

The New Nobility of Lying – Or What’s Left of It

“Because Telling the Truth Is Just So 20th Century.”

By Mika Horelli

What happens to democracy when voters no longer care whether their leaders lie? What if dishonesty becomes a virtue rather than a vice, not a dealbreaker, but a selling point? This essay begins with a Nordic anecdote about dignity and truth, and ends in the present, where shameless deception is no longer a liability. It’s currency. And increasingly, it’s the only one that circulates.

When Mauno Koivisto, who would later become Finland’s ninth president, was appointed prime minister for the first time in 1968, he received what he later described as one of the most important lessons of his political life. It came from Tage Erlander, Sweden’s long-serving prime minister, and it was disarmingly simple: “Never lie. If you start lying, you’ll be caught eventually – and no one will ever trust you again.”

That advice, once a cornerstone of Scandinavian political culture, now sounds almost quaint. In 2025, politics seems to have reversed the formula. Lying is no longer a last resort. It’s a strategy – and sometimes, the surest path to power.

So as not to sound completely naïve, I should note, like any reasonably informed political observer, that breaking campaign promises is so common that it’s hardly even worth calling it lying anymore. Circumstances change in politics, and in multi-party democracies where coalition governments are the norm, nearly everyone ends up stretching their promises. It’s part of the everyday reality of democratic governance, and every engaged citizen should treat campaign pledges, at least a significant portion of them, as directional rather than binding.

The situation is entirely different when a politician’s entire career is built on systematic lying – and yet they’re elected to office again. At that point, we have to start questioning the motivations of the voters themselves.

Tage Erlander wasn’t preaching morality. He was giving practical advice. Lying, he warned, isn’t just unethical – it’s inefficient. You need a sharp memory to keep your stories straight. Truth, on the other hand, is easy. You have to remember what happened.

In postwar Nordic democracies, truth wasn’t merely a virtue but an operating principle. Coalition governments depend on trust. So do voters. A leader caught lying wasn’t just exposed – they were disqualified. Not always legally, but politically. The breach of trust was the real crime.

That’s what makes the current moment so jarring. It’s not that politicians lie – they always have. What’s new is that many now lie deliberately, routinely, and without consequence. In some cases, they’re even applauded for it; the more brazen the lie, the louder the cheers.

Donald Trump didn’t just lie during his first term in office (2017–2021). He industrialised it so effectively that he was re-elected in 2024.

According to The Washington Post, Trump made over 30,000 false or misleading claims during his first term. FactCheck.org estimated he averaged more than 15 lies per day. When journalists pushed back, his aides gave them “alternative facts”; not as satire but as policy.

The truly remarkable thing? It worked. Trump’s lies didn’t weaken his base – they energised it. In the culture war he helped orchestrate, facts were no longer neutral. They were weapons of the elite. Truth had become just another tool of oppression. Lies were not a problem in that framework – they were proof of authenticity. Of rebellion.

Trump’s dishonesty isn’t a bug in the system. It is the new system.

The European variants

The virus wasn’t contained to the United States. Europe had its patient zeroes.

Nigel Farage, the architect of Brexit, famously claimed that leaving the EU would free up £350 million a week for the UK’s National Health Service. It wasn’t true, but it was printed on the side of a red bus and driven straight into political history. The lie didn’t damage him. It won him a referendum.

Now, 2025, Farage’s newest party, Reform UK, has achieved a notable breakthrough in recent local elections, sharply challenging both Labour and the Conservatives. The party managed to attract a considerable number of working-class voters, many from Labour’s traditional base, and secured hundreds of local council seats.

Boris Johnson was a well-documented fabulist long before entering Number 10. As a young journalist in Brussels, he built a career inventing absurd stories about supposed EU regulations – curved bananas, condom sizing, vacuum cleaner wattage. The stories were false, but highly effective. They stoked British indignation and sold papers. Later, they won elections.

By the time Johnson became prime minister, the public already knew who he was. A liar, sure – but a charming one. A rascal. A familiar character.

Consequences? None. The lies had become part of the brand.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Nordic Ledger by Mika Horelli to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.